Urban planning in the 22nd century

06 Jan 2020I read a great deal of Jules Verne as a child - practically all the books I could find. One book I did not get to was “Paris in the Twentieth Century”: written in 1863, first published in 1994 (so too late for my Verne phase). From a strictly business perspective, the editor was right to refuse publication, since it might have seriously damaged Verne’s earning prospects. And yet how curious is it that a (dystopian) book from the time of Napoleon III could get about two dozen major things right about the 1960s!

Along the same lines, I’m wondering every now and then what cities will look like in the 22nd century. Here’s what I think in terms of population trends:

1) Three generations down the line, the population (anywhere, but definitely in Europe and East Asia) will be significantly older and more health-conscious. The median age in Germany is over 47 today (43 for the EU as a whole) (2018 estimates). This is likely to go up to around 60 or so. They are likely to be the most educated generation ever (perhaps as many people will have PhDs as have Master’s today; and a Master’s will be the new high school degree). They will have benefited from a century of medical breakthroughs that may well prove to be as important as the ones from the past century were for us. Communities that will have reduced mortality from cancers and coronary disease by >95% will probably reach a life expectancy of around 120.

(I’m assuming that this is a generation decades removed from the current obesity crisis, living in a world where nutrition looks very different.)

2) The economy will be largely electrified and nuclearized, benefiting from another century in battery and reactor design improvements. By then, fossil fuels will be of only specialty use. In general, the world will be energy and computing power-rich.

3) The trend towards denser, larger cities will continue. Today there are around 100 cities with a population over 5 million (including metro areas); absent a large pandemic, these cities are likely to all grow beyond 20 million, and there will be, of course, more cities added to the list.

4) The global economic order will likely remain the same, which means humans will fall, by and large, within the same income categories as today. The wealthiest will own the most prestigious properties; the underclass will live in shantytowns or on the street; but urban planning will continue to make a massive difference for the few billion humans pertaining, no matter how tenuously, to one of the many layers of the middle class.

5) New climate patterns will wreak havoc on large parts of the world, which means international borders may become fortified to lock out climate refugees. Peak world travel and migration is likely today.

What this means in terms of urban planning:

1) A trend towards ever smaller habitation units. First of all, because arable land will increase in value; secondly, because as the older generations (“wealth hoarders”) live ever longer, new buyers on the market will be able to afford even the tiniest units only well into their 60s and 70s; thirdly, because robotization and continued delocalization will keep wages relatively low; fourthly, because current levels of wealth inequality, absent societal collapse, will likely continue or increase; fifthly, because of a shift in culture determining an increase in communal living as singles (dorm room style or asylum style); sixthly, because of increased density on a background of slowing but still ongoing population increase.

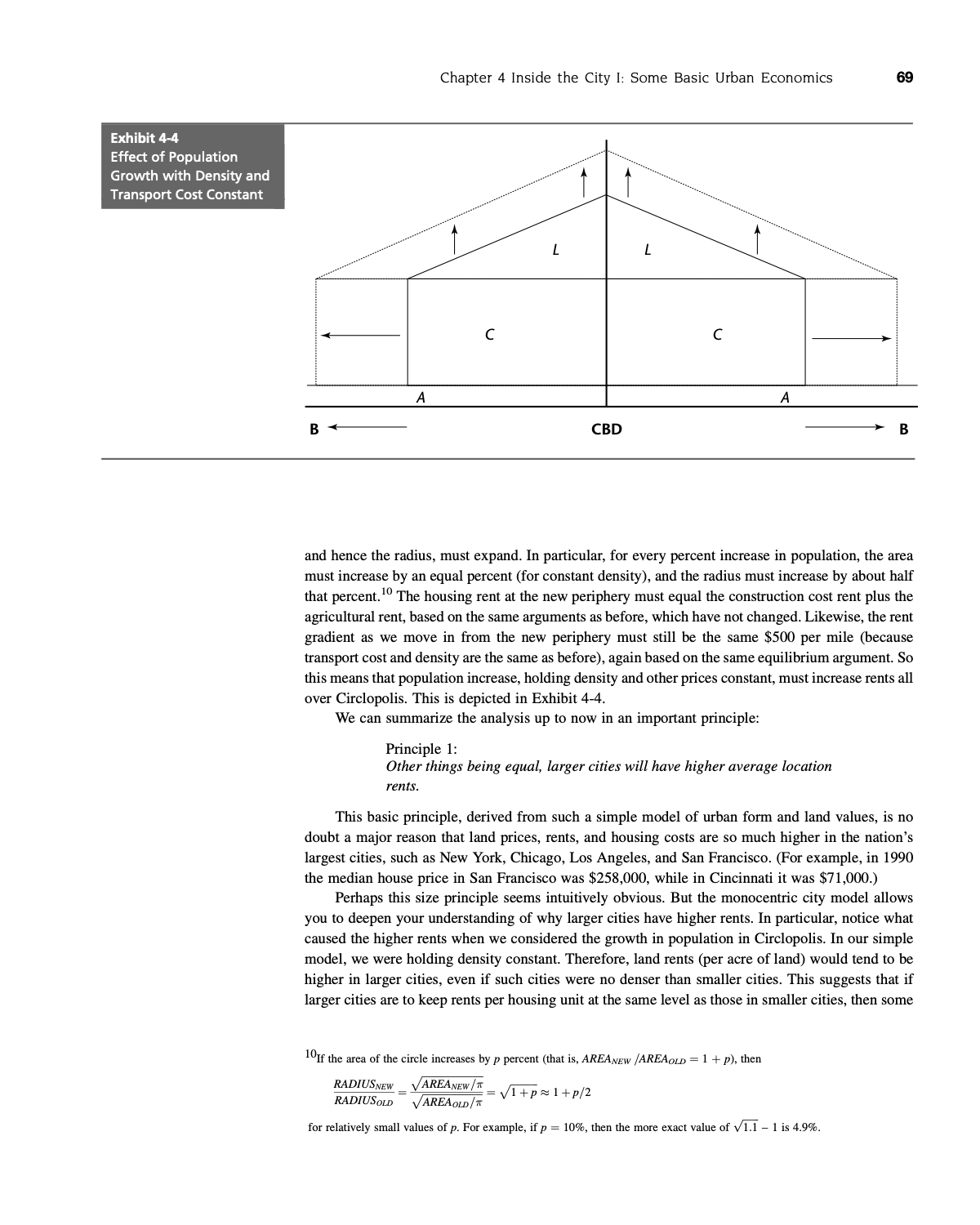

As a side note, I think the dominating effect will be that of ever decreasing purchasing power on the background of ever increasing cities. The first principle of urban economics is essentially that rents paid increase proportionally with city size (source: Geltner et al.’s Commercial Real Estate Analysis and Investments):

2) A trend towards global planning. Historically, planning was mostly done at the neighborhood and city level; when ambitious, at the regional level; and when well-paid, at the micro-neighborhood level.

The trend towards more planning will continue until it encompasses all levels. Climate change catastrophes should compel world governments to agree to some sort of global planning framework by then (the Spaceship Earth model: it’s the only spaceship we have, resources are limited, no one should be allowed to set fire to our ship or consume resources unfairly). Negotiations should start in earnest once fires and floods shave off around 10-20% of world GDP, if distributed relatively evenly (the US and China and India and the EU and the Middle East have to be hit very hard; the world will likely see action only when the portfolios of most wealthy shareholders will take serious damage).

3) Planning will also happen at the individual level. Individuals are heavily self-segregating today, and with an enormous increase in public data, and another century of privacy erosion (until privacy may well mean something very different for today), we’ll be able to know our neighbors as never before. Couple this with ever more sophisticated sim city models and you have micro-planning: optimizing for lots of variables when you know everyone who lives in a city (by name, social media history, biometric data, health data, mapped genome, purchasing power), available construction materials, weather patterns, preferred home furnishings, and most common destinations for each individual (based on a life history of movement). The urban environment will be fully tracked, monitored and modeled (simulated copies of cities will be running on both public and private servers at all times - to improve public policy or find profit opportunities).

In any case, people will spend as many hours or more immersed in virtual reality as they do today on their smartphones. This will improve a government’s ability to assuage its population, since improving a virtual environment is far easier than improving physical infrastructure (a person’s eyes and hearing will likely be engaged by virtual artifacts 90% of the time, and by the built environment only 10% or so). Mass protests in person will be a thing of remote history (in most countries, they already are: the youth today shares angry posts on social media, but they are usually too disillusioned, cynical and atomized to organize real life protests). In any case, police technology has all but eliminated the possibility of forcing policy change through street presence. In the world’s largest economies (US, China), meaningful mass protests are unthinkable absent societal collapse.

4) A trend towards custom-built communities. Historically, a building was first designed in anticipation of market trends, then built, then leased/sold off. Recently, finding tenants has begun happening post-design, but prior to construction (to minimize risks). It’s likely that tenant acquisition will move to becoming the very first step (through big data sifting and offering customized offers within a virtual environment to the likely takers, then negotiating the design and financing within that environment).

Increased robotization should mean that structures become ever more modular, with tenants able to customize certain elements (on the order of 10% or so). In many ways, it will be back to the past (lower incomes and longer lifespans - as frail individuals - will reduce resource consumption per capita). In some ways, humanity will attempt to become post-biological (we may see people start to heavily rely on implants for everything: physiological health, social life, economic productivity, as laptops, smartphones, and smartwatches enter the human body).

5) The design language will fall into a few large families, already discernible today. Firstly, low-cost housing for the poorest of the middle class (the 22nd century equivalent of Brutalist apartment blocks) - we have a preview of this in Hong Kong. Secondly, neo-corporate towns - glass, steel, and total surveillance (the equivalent of medieval monasteries, with corporate drones as monks, studios as cells, and corporate officers as abbots, priors, and sacristans). The larger ones will also be inhabited by the owner class, and will thus be equivalent to the medieval citadel monasteries (the new lavish apartments in the inner keep for the nobles). Thirdly, retro-urban developments, variously themed (e.g. Spanish colonial or French Belle Epoque).

6) The anchors of a neighborhood will switch from visual to conceptual (based on ownership). Traditionally, neighborhoods were organized around a common destination/utility (cathedral, opera house, market, factory - all instantly recognizable). With work, shopping and social life transferred to virtual environments, fewer anchors will be built.

Generally, the visual landscape of the 2120s should be recognizable to people today, much as Paris and NYC are not too different now from what they were in 1920. The only question is what forms of development will proliferate (easy answer: generic apartment buildings) and which ones will diminish (easy answer: single family housing).

I will likely be alive for the first 50 years of all this; I’ll do what I can to speed up the good developments, and slow down the bad ones.